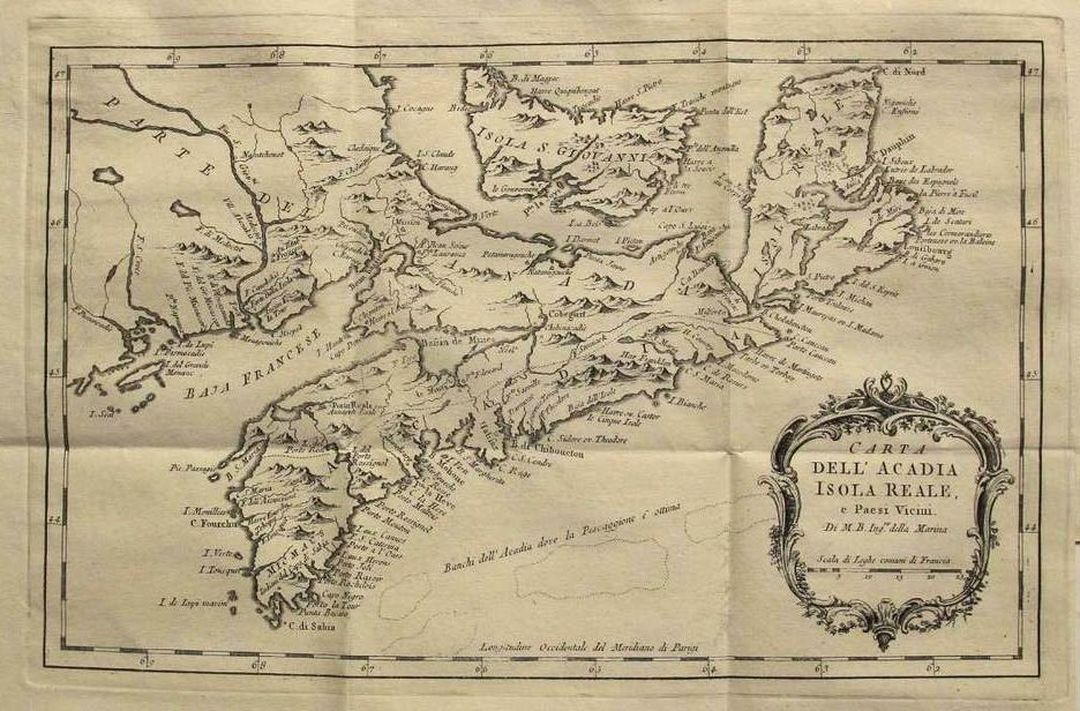

(above): 1785 map by Bellin, Italy. copper engraving. Note the detailed drawing of River Inhabitants and the Basin.

Location

The River Inhabitants is born out of tributaries from the hills of Creignish and Kingsville, Inverness County. These tributaries join to first form two branches of the River Inhabitants in Kingsville which join together at Princeville, Inverness County, near the Rooyaker Egg Farm. The main river then flows down through the communities of Princeville, Riverside, Cleveland, Grantville, Hureauville, and Lower River Inhabitants/Evanston to join Inhabitants Bay, known locally as River Inhabitants Basin or Whiteside Basin.

Settlement:

The French

The land along the River Inhabitants was first settled, in the early 1600’s, by the French from France and some Acadians from mainland Nova Scotia, when Cape Breton Island was owned by France and called Ile Royale. This was done under Sieur de Mont, and the settlers known to the French Government officials as habitants, were supplied by that government with tools, seed, food enough for two years, and farm animals to begin their farming along the river. That is why the river was called Riviére des Habitants, now known in English as River Inhabitants. At that time some family names to be found along the river were, Boudrot, Boucher, Decoste, Fougére, Hureau, Landry, LeBlanc, Nagereau, and Richard

After the last fall of Louisburg in 1758, when Ile Royale became Cape Breton under the English, the English Government’s policy of expelling all Acadian and French settlers was extended to the island. However, this phase of the expulsion was less successful than that carried out on the mainland from 1755 on, because the Acadian and other French settlers on Cape Breton knew what had happened on the mainland. Therefore, when the settlers saw British Man-of-war Navy ships or any other ship flying a Union Jack Flag coming into sight, they fled into the woods, if they could do so, and remained there until the ships and any British soldiers had gone. Only a small number were captured and expelled. The others, however, could not always return to their farms, for farms along the River Inhabitants were burnt by the British on their way to lay siege to Louisbourg. From Riviére des Habitants the British took all the animals and stored food crops to supply their siege against Louisbourg. All the settlers or descendants of the settlers, who were burnt out, had to spend their winters in the lodges of the Mi’kmaq, who were their friends, and often relatives. The next spring the settlers would leave their hosts and go to Ile Madame. On that island the Acadian and the French settlers were not being expelled. The French Huguenots, like the Bourinots, Levescontes, Ameys and Georges, who were allies of the British and used the Catholic Acadians as workers, requested that their workers not be expelled, and were granted that request. There the refugees would blend in with the population. After the threat of expulsion, had passed, they and their descendants were able to settle back on the main island of Cape Breton at places like Louisdale, River Bourgeois, etc.

The Loyalists

With the removal of the French settlers from along the Inhabitants River, land became available for settlement by people considered to be more sympathetic to British rule. These settlers were the Empire Loyalist, who had fled persecution of the citizens of the new United States of America during and shortly after the American War of Independence (American Revolutionary War). These new settlers, many of whom were first given grants of land in Eastern Guysborough County, then known as Manchester, demanded good farmland, and were given grants along both sides of the River Inhabitants. Grant, King, McCarthy, Oliver, Proctor, Redmond, Upton and Whalen, were Empire Loyalist families to be found on those grants. The descendants of these Loyalist families can still be found within the

communities of Evanston, Grantville, Hureauville, and Whiteside.

Acadian Return

Shortly before and after the arrival of the Loyalists, some of the Acadian families had made their way back to a part of the River Inhabitant Valley, where they established small farms and did some fishing in the river. Hureauville, named after one of the families that resettled there, is the community under discussion. DeCoste and Richard were the other families that resettled in that community.

Just north of them, over the hill was Grantville, a largely Protestant community of Scottish settlers, which was using a cemetery containing the remains of some of the French settlers, who had lived in that area prior to the expulsion and burning previously mentioned. Frequently, while digging graves to bury deceased Protestant persons from Cleveland or Grantville, those doing the digging would uncover the deceased’s skeleton remains with rosaries or crosses, positive evidence of the existence of the previous French settlements. Some of the descendants of the Acadians who returned to the area, plus others from Isle Madame and Louisdale married in with the English speaking residents, so that now many residents of the community area are of mixed ethnic background. As well, within the last three decades, families of Acadian descent from the Petite de Grat area, whose forefathers may well have lived in the Inhabitants River area in previous centuries, have relocated to the area.

The Scots

Along with the resettlement of the Acadians and the grants to Loyalists, came the settlement of some Scots families like Ferguson, MacDonald, Malcolm, some of whom left Scotland because they were pushed out by greedy Lairds, who wanted their holdings for the raising of sheep -- a shameful time in the history of Scotland, known as the clearings. Descendants of these Scot settlers can still be found in the communities along the Inhabitants River, in Kempt Road, and in Walkerville and Whiteside, which are along the shore of Inhabitants Basin.

The Irish

In addition to the groups of settlers mentioned, came the Irish at the very beginning of the 1800’s. These were the refugees from the Wexford Uprising (rebellion) of 1798 who, in hiding from the British authorities, settled well back in the woods bordering on the Inhabitants Basin, until it was safe to move nearer the shore of the Basin. These refugees, most of whom settled in Rocky Bay, Richmond County, and the Margarees in Inverness County, had reason to be fearful under the Penal Laws.

Not only were their lives to be extinguished as traitors for daring to fight against the British crown, if they were unfortunate enough to be discovered by the authorities, but, according to British Penal Laws, it was illegal for them to be in British North America. These refugees were represented by the families of Doyle, Cloak, Dunphy, Hayes, Lamey, Morgan, possibly Scanlan (formerly Scantling), possibly Tyrrell (formerly Farrell), Welsh and White.

Only the family names of Doyle, Hayes, Morgan, Scanlan, and White families can still be found in the Basin - River Inhabitants communities today, though the genes of the others flow in the veins of both these, as well as in the veins of the Loyalist descents, of some of the Scottish descents, and of some of Acadian descent. The Cloaks and the Welsh’s moved away from the area, with the remaining old people dying out. The Tyrrells and the Dunphys moved to the Isle Madame area during the early 1900’s.

Some of the Irish of Whiteside had a connection with President John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s mother,

Rose Kennedy. She was born of a Wexford Uprising refugee family, the Fitzgerald family, and was actually a cousin to the Basin Road, Whiteside, Doyles* and Morgan families. Both families were descendant relatives of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, one of the most important leaders of the 1798 Wexford Uprising. The Morgans and Doyles were descendants on their mother’s side, Mary Fitzgerald, while Rose was a descendent on her father’s side. It wasn’t only because he participated in the uprising, that Mary’s son, Edward John Morgan Sr., spent the remainder of his life as a refugee hiding deep in the woods of Basin Inhabitants on a hundred acres. As close relative of Lord Fitzgerald, Edward Morgan, he believed that the Amnesty of 1803 did not apply to him, and that the British would hang, draw and quarter him, if he were to be caught. Indeed, back in Ireland all the Morgans left in Limerick had been vengefully exterminated by the English forces after the put-down of the uprising. Long after the Amnesty and their father’s and grandfather’s death, his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren kept the secret. The history of Ireland has Edward John killed at the Battle of Vinegar Hill, outside Wexford Town. If they ever knew, Ireland’s historians seem unaware that such a large number of 1798 Wexford Uprising refugees had escape to the new world, many with the help of the people from Scotland.

*It is through intermarriage with the Morgans that the Doyles can also claim descent from Lord Fitzgerald.

The most common Irish name, McNamara, to be found in the communities of the The Basin and River Inhabitants, is not one of the refugee families but are descendants of a David McNamara, who arrived in Guysborough County from Boston around 1784 - 1790, the same time as did the Loyalists, and married a Sarah Hall at Halifax,. McNamara settled, with the permission of the then General, on Boucher Island in the Basin Inhabitants. After two attempts, first as an Irishman and secondly, five years later, as a Scotsman, he was granted the island which was renamed McNamara Island. There the McNamara first multiplied and flourished, until the island could no longer support their numbers. Many of them then moved over to Evanston and Lower River Inhabitants, though a number of them moved to the United States, looking for employment. The notable Senator Robert McNamara, of the United States Senate, proudly claimed his ancestral roots in Lower River Inhabitants, Nova Scotia. McNamara Island no longer has full time residents.

Industries

Up until the early 1900’s, the communities around the Inhabitants River prospered. Many of the Proctors, some of the Malcolms and the Walkers owned clipper ships and sailed around the word in trade. The last two families ran very prosperous retail business and shipping businesses within their communities. All the other people of the communities worked in various venues: for ship owners or merchants, fished, farmed and lumbered for a living; or worked in the Richmond Coal Mine in Lower River Inhabitants, which operated until burnt out by a forest fire in 1936; or were involved in all of the first four industries, even supplying pit props for the mine. A coal mine by the name of Tide Water Coal Mine also operated for as short number of years on two separate occasions from 1928 in lower Whiteside, but was flooded out by underground water on each occasion.

The Morgans, Doyles and the Dunphys ran water driven saw mills and the Morgans and Doyles also jointly operated a water driven grist mill. A Rory Dunphy, before moving away, even ran a saw mill off a huge raft chained in the Inhabitants River. Forges also flourished in the area under both the Fergusons and the Morgans, and many of the men from most of the families were skilled carpenters who built not only in their communities, but also in Port Hawkesbury, Port Hastings and around Isle Madame.

Even after sailing ships were no longer considered as commercially viable, most of the people earned good livings in the industries mentioned. Only during the depression of the 1930’s did a few of the families need social assistance.

Due in part to the traditional Celtic interest in education, a trait shared with the loyalists, the average education levels within the communities were fairly high and there was a good work ethic. This was a significant factor when the big industries of pulp and paper (Stora Forst Industries), the Gulf oil refinery and heavywater were established at Point Tupper, Richmond County. There were very few men and women of the communities who did not find employment. The vast majority became employed in those industries or in the related retail industries. As a result, most of the residents have a comfortable living with a good number now retired on substantial pensions.

Community Names

The names of the various communities in the River Inhabitants and The Basin area came into being when the rural post office system was established, the one exception being Evanston.

Archie Walker of what is now known as Walkerville took a petition around his community to get that community called Walkerville as a postal address, while Cleveland had its name established by an act of the Nova Scotia Legislature at Halifax. Grantville and Hureauville were obviously named after the most prominent founding families of those communities, while the postal address of Whiteside came from both the fact that the White family populated that community with few exceptions, and the railway siding and station then maintained by the Cape Breton Railroad under the name, Whites Siding, later changed to match the postal name, Whiteside. The postal name Lower River Inhabitants has an obvious genesis, since that community is located near the mouth of the Inhabitants River.

The name of Evanston was born out of a bureaucratic blunder by some provincial civil servant in Halifax. The intended name of the place was Evans Town, a name that came into being when the Cape Breton Railroad needed a station name for what is now Evanston. The railroad company intended to honor its principal shareholder by naming what they believed would become a town, as a result of the railway business. However, a civil servant, sometimes during those early years, miscopied the name onto official documents, which enshrined the mistake for posterity. When the granddaughter of the original shareholder came to visit the community in the early 1920’s, she was disappointed to discover that the name had been changed. However, her disappointment did not inhibit her from investing huge sums of money into a water flooding coal mine known as the Tidewater Mine at the southern end of the Inhabitants Basin. So much of the coal taken from that mine had to be used to fuel the three steam engines that operated the five pumps, which were continuously working to reduce the flooding, that the mine did not operate after 1932. The Tide Water Mining Company went bankrupt and Miss Evans lost her investment.

The Railway

The railroad, frequently mentioned, was a major construction project in the late 1800’s, for it involved the construction of a huge trestle bridge over a fairly wide part of the Inhabitants River. During the construction of that bridge, a donkey engine steam engineer was drowned in the river, when his engine toppled of its tracks. Both the engine and his body were recovered many kilometers down the river, which shows the strength of that current. My late uncle, Percy James Proctor, also claimed that a Chinese immigrant worker also died during the construction and was buried in an unmarked grave beside the railway.

As a child, I often walked across the trestle bridge during times when the train was not chugging along the rail bed. Years before and after my ventures across, many other people also did. The railway rails and ties have been gone since the late 1970’s, and all that remains of the trestle are its concrete buttresses, which can be seen looming out of the water to the right of anyone crossing the Lower River Inhabitants bridge as they travel towards Port Hawkesbury on Highway 104.

Religion

The settlers of the Inhabitants were either Roman Catholics or Methodists, with a very few Anglican families. The latter eventually joined either the Methodists or the Catholics through marriage or conversion, when those religious denominations built Churches in some of the communities.

It is not known if the first French settlement along the Inhabitants River had a church, which would have been burnt by the British, but the likelihood is high, since they had a Catholic cemetery, which is now the United Church Cemetery in what is now Grantville. A grave containing the bones of a woman with the remnants of a rosary was found in the late 1800’s, while a grave was being dug to inter a deceased Protestant. If there was a church, it must have been close by. Only archeological digging may find substantiating evidence.

Those persons, who settled the area under British government, did not build central houses of worship until the mid-1800s. Worshipping was done in a selected home of one of the communities, when a priest or minister would visit from Guysborough, Isle Madame, or later Creignish. Marriages at first, except for those who traveled long distances to either L’Ardoise, Arichat, or Creignish, were common-law until such time as a visiting priest or minister arrived to bless the unions and establish legal recognition of the same. It was during the visits of the ministers or priests that baptisms were performed on the latest arrivals, or communion was the given and the sacrament of Confirmation was administered to those who were eligible for the same.

Those of Scottish, English, or Acadian descent could have built churches, if they had wished to, and had the funds or materials and/or skills to do so, but the Irish Catholics were prohibited from doing so under the British Penal Laws. These laws not only made their very presence in the area illegal, but forbid their building houses of worship. It wasn’t until the final penal law was repealed by the Nova Scotia Legislature in 1835 that those Irish could commence building. This last repeal saw the construction of the first Saint Mary’s Basilica in Halifax, but building elsewhere was at least fifteen years later. When their relatives, the Doyles and other Irish Catholics of Northeast Margaree began the construction of St. Patrick's Church in that community by building first the vestry as a place of worship, the Doyles, Morgan, MacNamaras, Whites, Scanlans of River Inhabitants Basin followed suite. Then in 1855 both communities, which were in communication with one another through exchange visits between relatives, began the building of the main body of each church. The Whiteside St. Patrick’s Church was opened officially for worship in the 1860’s, though services had to be supplied by the priests of neighboring parishes.

This was so until 1906, at which time a social disagreement between branches of a family took place in the church prior to Christmas Eve mass. The priest, who was from the neighboring community of Louisdale, walked in on the incident, which he considered a desecration of the church, causing him to proclaim that there would never be another Christmas Eve mass in the church. The following Christmas Eve saw no mass, and on February 6, 1908, in the early morning, the building was struck by lightning and burnt to the ground. Only the altar and a matching candle stanchion were saved. Both items were stored next door in the barn of Michael John White, in expectation of a new church being built.

By 1912, the residents of Whiteside had accumulated enough money to begin the construction of a second St. Patrick’s. Daniel O’Connell Doyle and his third oldest son, Edward Daniel Doyle took on the job of construction. Since the building was being done in opposition to the will of Reverend Father Angus Beaton of Port Hawkesbury, who had become pastor of the missions of Lower River Inhabitants and of Whiteside in 1910, and who had been by passed by the Whiteside men when they went directly to the bishop to get permission, the resulting building was different than the original. Father Beaton reduce the planned dimensions of the new church by one yard (0.91 m) in both length and width, and had them build the church facing River Inhabitants Basin. The first change reduced the building to a size that would exclude it ever from becoming a parish church, making it uncomfortably small for the size of the congregation, if all were in attendance. The second change resulted in a picturesque church facing a beautiful body of water and being against the background of a very high, forested hill. The building was consecrated in 1922, but regular Sunday mass was not held in it until 1936. Until that time, to meet their Sunday obligation, each resident had to walk or ride by horse and wagon, or horse and sleigh, past their own church, for a distance of nearly five miles { 8.3 km ) to be then ferried across the Inhabitants River, first by boat and later by cable ferry, and to then walk an additional three quarter mile { 1.25 km }, a total of 5.75 miles ( 9.58 km } to the St. Francis de Sales Church at Lower River Inhabitants. For those without horses, being forced to travel that distance on foot each Sunday was a heavy sacrifice.

On a sunny Sunday in the summer of 1936, Bishop Morrison of the Diocese of Antigonish was approach by a representative group of men from Whiteside: Daniel O’Connell Doyle, Michael R. Morgan, Joseph Roderick MacDonald, William Daniel. White, Michael John White, Duncan A.White, and Ambrose White. Bishop Morrison was at Port Hawkesbury to administer the sacrament of Confirmation to the eligible youth the Port Hawkesbury Parish of St. Joseph’s and the neighboring missions. On being approached by this delegation with the request to have Sunday mass regularly said at St. Patrick’s, the men often quoted the Scots bishop as saying, “What do you want to do, kill your priest?’ One of the men explained that they were not seeking to kill the pastor, Father Angus Beaton, through exhaustion, but they felt it was more than equally unfair to expect people to walk a considerable distance past their own church building to attend Sunday mass in a neighboring mission. The bishop agreed with their argument, but did not wish to place a greater load of duties upon Father Beaton. The solution was to reinstate St. Francis de sales as a parish. Father Alexander J. MacDonald, Father Beaton’s curate (assistant priest) volunteered to become pastor of the new parish. The bishop agreed, and St. Patrick’s Church finally had Sunday Mass, and continued to do so except for six months from October, 1969, to May of 1970, when there was a closing of the church through an unfortunate misunderstanding. The then bishop, Most Reverent William Power granted the reopening of the Church, and has had weekend mass with very few exceptions.

The Protestants of the area did not have to seek the permission of either a bishop or a minister to build their church, nor did they have to have fund raising. A wealthy Methodist merchant, William Malcolm of Port Malcolm agreed to meet the wishes of his fellow Protestants by paying for the building of a new Methodist Church at Port Malcolm, where his family and his prosperous store and shipping business were located. This church opened in the 1830’s and continued to serve the needs until around the late 1940’s. During that time it changed from being a Methodist Church to being a United Church, because the Methodist was one of the churches in Canada to join with the Congregationalists and some of the Presbyterian Churches to form the United Church of Canada.

The spirit of ecumenicalism was alive and strong along the river and the basin in the 1800’s. This was due in part that there were many marriages between Protestants and Catholics, and many of both faiths were related by blood.

The Roman Catholics from the communities along the eastern side of the Inhabitants River also received financial help from the Port Malcolm merchant, William Malcolm, in the construction of their church, St. Francis de Sales. Mr. Malcolm was married to a Catholic, Bridget Proctor of Lower River Inhabitants. When Joseph (Joe) Hureau of Hureauville approached Mr. Malcolm for a donation towards the construction of a Roman Catholic church, he was informed that Malcolm’s donation would be a dollar for dollar match for whatever money Joe collected from the Roman Catholics. Hureau did his part and Malcolm provided the other fifty per cent of the money.

The present St. Francis de Sales Church, which is also the original church, was built and consecrated as a parish church in 1875. This operated until 1909, having to that date as its last pastor, Reverend Father Maurice Thompkins, who was a first cousin to Reverend Father James Thompkins and to Reverend Father Moses Coady, the two leaders who found the Antigonish movement.

Father Maurice Thompkins was transferred to Guysborough around 1909, and St. Francis de Sales, along with the communities of Evanston, Walkerville and Whiteside who had lost their St. Patrick’s Church to fire in February of 1908, was made missions of St. Joseph’s at Port Hawkesbury. Reverend Father Angus Beaton became their new pastor and ruled his new charges until 1936. In that year, a delegation from Whiteside approached the bishop, after confirmation service at Port Hawkesbury, to get Sunday mass established in their new, fourteen year old St. Patrick’s Church.

The bishop decided he could only grant their wish by reestablishing St. Francis de Sales as a parish. Reverend Father Alexander (Alex) J. MacDonald was appointed as pastor, a position in which he remained until July of 1950. He was then transferred to St. Lawrence’s Parish, Mulgrave and replaced by Reverend Father Michael Stevenson, who in turn was replaced by Reverend Terrence Powers in 1954. Father Powers was replaced by Reverend Joseph Campbell Two years after his transfer from St. Francis de Sales, while working for the St. Francis Xavier Extension Department, Father Campbell left the priesthood to become a layman and a parent. Father Campbell was replaced by Reverend Father Edward Tobin, who also became an educator at the Isle Madame District High School at Arichat.

During his pastorship, Father Tobin directed the renovations of the St. Francis de Sales and the St. Patrick’s churches to bring them in line with the changes demanded under Vatican Council II. During this time, a bridge was also constructed over the Inhabitants River, making travel between Whiteside and Lower River much easier. With this change, Most Reverend William Power, Bishop of the diocese, ordered Father Tobin to see to the closing of the mission church of St. Patrick’s at Whiteside. Except for very few on the parish council, the parishioners of that mission were not consulted about the proposed change, and were astonished on a Sunday morning in October of 1969 to be told there would be no more masses at St. Patrick’s. The change split the communities of Evanston, Walkerville and Whiteside into two camps: those accepting the change and those against. The latter were greater in number, and withdrew their financial support of the St. Francis de Sales Parish. These angry parishioners attended services at Louisdale, West Bay Road or Port Hawkesbury instead.

Father Tobin, whom the bishop allowed to be the scapegoat for the schism, quit the priesthood, finished teaching the school year at IMDH, and moved to teach in Montreal, where he later was laicized and got married. A week after Father Tobin’s resignation, Reverend Father James MacIntyre was appointed pastor to St. Francis de Sales only. Father MacIntyre found his parish to have little financial support, since the majority of his parishioners had withdrawn their financial support over the church closing. However in April of 1970 a delegation of men from the St. Patrick’s faction met with the Bishop at the retreat house in Gardener Mines. At that time the bishop learned of the true feelings and ambitions of the offended people, and granted the reopening of St. Patrick’s Church under the same conditions as before. The St. Francis de Sales Parish once again became whole, with financial support being restored. However, some feelings of distrust lasted for some time on both sides of the issue, and future Parish Councils had to take care to give due attention to both churches.

Since the time of Father MacIntyre, the Parish of St. Francis de Sales has had as its pastors Reverend Father Terrence Lynch, Reverend Father Francis Delhanty, Reverend Father Robert Wicks, Reverend Father Robert MacNeil, Reverend Father Joseph MacLean, Reverend Father Paul Murphy, Reverend Father George MacInnis, Reverend Doctor Donald Campbell (fill in pastor for nine months), Reverend Father Peter MacLeod, and the present pastor, Reverend Father Allan MacPhie.

Education

When the area was first settled, there were no schools in any of the communities. Until 1880, anyone wishing to learn to read and write and to learn to do arithmetic had to learn at home, if a parent were educated enough to do so, or travel to St. Peter’s or some other larger community where a school had been established. My great-grandfather, James Robert Proctor had to stay for a couple of years with his mother’s sister, Mary Critchell Murray, in St. Peter’s so he could learn to read and write and to study arithmetic.

In 1880 a one room school was built at the most southern end of Lower River Inhabitants and two years later another such school, called the French School, was built between Grantville and Hureauville, to serve both communities. It was called the French School, because most of the students were French speaking Acadians from Hureauville, and the teachers at first were bilingual from Arichat.

By 1885 another one room school was built between Walkerville and Evanston, to serve those communities. The last private banker in Canada, Gordon Walker of the Walker Bank at Port Hawkesbury, located near the present Royal bank, received his basic education at that school. He used to pay ten cents to one of his classmates, Gregory McNamara, who helped him understand arithmetic better. A newer two room schoolhouse, the Walkerville-Evanston School, was built closer to Evanston, replacing the one room schoolhouse in 1949. Both my mother, Vida Proctor Morgan and I spent a number of years teaching at that school. The school was permanently closed in June, 1966, the second year after I left the area. The elementary students attended the old white multi-room school in Louisdale, with the junior high and high school students attending the new Isle Madame District High School at Arichat. This arrangement continued until June of 1979, after which time the primary through grade eight grades began attending the new Walter Fougere Elementary Junior High, which I, as chairperson of a building committee, was very instrumental in helping to bring into existence. This school, later the Evanston Site of the West Richmond Education Center, served grades five through eight until its closure at the end of June 2013.

Whiteside and Cleveland each got a one room school by 1890, both built from the same plan by a Joseph MacDonald, a carpenter from Antigonish Harbour, whose sisters had married in the Whiteside area; Sarah MacDonald was the first wife of E. James Doyle, and Jane was the wife of Timothy White. The Cleveland School operated until 1966, with the late Marcella MacCuish as the last teacher. The elementary and junior high students then attended the Point Tupper School with the high school grades attending Port Hawkesbury High. The Whiteside School continued until 1957 with Laura Hearn being the last teacher. The students then attended the old Louisdale white multi-room frame building previously mentioned, with high school students attending Arichat Convent School. When the Isle

-9-

Madame District High (IMDH) opened in 1966, serving grades seven through twelve, while the elementary grades attended school in Louisdale. With the opening of the Walter Fougere Elementary-Junior High in September of 1979, all the Whiteside and Evanston students in primary through grade eight transferred there. Grades nine and up were still at IMDH.

Initially the teachers of the one room schools had little more education than the students whom they taught. For example, a student might graduate from grade ten one year, and be the teacher of the same school the next year. Sometimes, young ladies from other communities would come to teach at those schools. These teachers were boarded in suitable homes within the respective community and would be paid maybe $200 a year, depending on the prosperity of the community and the collecting of taxes for that year. Sometimes they were not paid at all or pay years later, when money became available. Later the amount rose to $500, but this money could also be slow in coming. After 1947, the NSTU helped the teachers of Nova Scotia get more acceptable salaries on a more regular basis, with salaries becoming successively better on from the mid 1960’s.

A way of contributing to the support of the teacher was to have her or him change boarding houses each month, so the provision of board would be considered part of the contribution from the respective community members. My maternal grandmother, who was bilingual, with River Bourgeois French as her mother tongue, boarded the Lower River Inhabitants teachers on an annual basis. Since many of these teachers were French speaking also, my mother and her siblings learned to speak in a French environment, with French becoming their mother tongue. Their English speaking father was often away working on the railway. The youngsters learned to speak English when their father was home, so they all grew up being bilingual.

One man who taught in the one room schools of Richmond County was Mr. Scott Nelson. Mr. Nelson taught in Point Tupper, Whiteside and Louisdale in the early 1900’s. While at Louisdale, Mr. Nelson was instrumental in giving Louisdale its present name, for the former name of Barachois was a confusing postal address, with mail going astray between it and Little Barachois near Arichat. His suggestion to use the “Louis” part of the parish name as part of the new name was accepted when linked with “dale.”

At Whiteside, Mr. Nelson was a stern disciplinarian. Teaching was not an easy task with some country boys being quite mischievous. One day Mr. Nelson opened the outside door of the school, only to have a boy perched up in the porch rafters dump a galvanized bucket of ice cold spring water onto his bald head. The culprit was then sent to the woods to cut a strong switch for the beating he was to receive as retaliation for his offense. The offender had some days of discomfort when sitting down.

The arrival of lady teachers for the one room schools, not only contributed to the education of the respective community, but also eventually also to the populations of those communities. Very often the teacher was courted and became a married wife and mother within the community. For this reason some of the teachers had very short teaching careers. When I taught in Evanston in the early 1960’s, every second house had a former teacher as a mother. A very similar situation could be noted in the neighboring communities.

The heating of the one room schools consisted of a heating stove, often called a potbelly stove situated in the middle of the classroom. These stoves were fueled by either wood or coal, depending on the decision of the local school trustees. Frequently the laying of the fire and the lighting of the stove

were the duties of each teacher who might get help from the older students at times. It the school was drafty, those students farthest from the stove could be very uncomfortable, while those nearer the stove could become overheated.

In the earlier days of the one room schools, scribblers were not easily available, so students often did their writing on slate board, committing their lessons to memory. Later, the slates were replaced by a more plentiful supply of scribblers and lead pencils and fountain pens. Prior to the fountain pen, each desk had an inkwell bottle recessed into the desk surface. Into this inkwell, a straight pen with a metal nib could be dipped. Some boys, who were more interested in torturing some of the girls, also used the inkwells for braid dipping; an action not enjoyed by the victims.

Despite all the difficulties, learning did go on, as it does in classrooms of today. The numerous grades within the same room, created a family like learning environment, in which older students helped younger students, younger students .listened in on the work of the older students, readying them for the next grades, and students who didn’t understand the instructions from the teacher could turn, in many cases, to other students who might be able to better explain. Many well educated individuals came out of the one and two room schools of the communities around the Basin-River Inhabitants area. Some were doctor, ministers, priests, nuns, nurses, school principals, college professors, and even university presidents and superintendents of schools in Ontario. As noted earlier, the levels of education were sufficient to gain employment for many when manufacturing industries came to the strait area.

. There is much more information that could be explored, but this is sufficient for a brief history.

Lester Morgan

March 22, 2001

Revised: August 6, 2017

Location

The River Inhabitants is born out of tributaries from the hills of Creignish and Kingsville, Inverness County. These tributaries join to first form two branches of the River Inhabitants in Kingsville which join together at Princeville, Inverness County, near the Rooyaker Egg Farm. The main river then flows down through the communities of Princeville, Riverside, Cleveland, Grantville, Hureauville, and Lower River Inhabitants/Evanston to join Inhabitants Bay, known locally as River Inhabitants Basin or Whiteside Basin.

Settlement:

The French

The land along the River Inhabitants was first settled, in the early 1600’s, by the French from France and some Acadians from mainland Nova Scotia, when Cape Breton Island was owned by France and called Ile Royale. This was done under Sieur de Mont, and the settlers known to the French Government officials as habitants, were supplied by that government with tools, seed, food enough for two years, and farm animals to begin their farming along the river. That is why the river was called Riviére des Habitants, now known in English as River Inhabitants. At that time some family names to be found along the river were, Boudrot, Boucher, Decoste, Fougére, Hureau, Landry, LeBlanc, Nagereau, and Richard

After the last fall of Louisburg in 1758, when Ile Royale became Cape Breton under the English, the English Government’s policy of expelling all Acadian and French settlers was extended to the island. However, this phase of the expulsion was less successful than that carried out on the mainland from 1755 on, because the Acadian and other French settlers on Cape Breton knew what had happened on the mainland. Therefore, when the settlers saw British Man-of-war Navy ships or any other ship flying a Union Jack Flag coming into sight, they fled into the woods, if they could do so, and remained there until the ships and any British soldiers had gone. Only a small number were captured and expelled. The others, however, could not always return to their farms, for farms along the River Inhabitants were burnt by the British on their way to lay siege to Louisbourg. From Riviére des Habitants the British took all the animals and stored food crops to supply their siege against Louisbourg. All the settlers or descendants of the settlers, who were burnt out, had to spend their winters in the lodges of the Mi’kmaq, who were their friends, and often relatives. The next spring the settlers would leave their hosts and go to Ile Madame. On that island the Acadian and the French settlers were not being expelled. The French Huguenots, like the Bourinots, Levescontes, Ameys and Georges, who were allies of the British and used the Catholic Acadians as workers, requested that their workers not be expelled, and were granted that request. There the refugees would blend in with the population. After the threat of expulsion, had passed, they and their descendants were able to settle back on the main island of Cape Breton at places like Louisdale, River Bourgeois, etc.

The Loyalists

With the removal of the French settlers from along the Inhabitants River, land became available for settlement by people considered to be more sympathetic to British rule. These settlers were the Empire Loyalist, who had fled persecution of the citizens of the new United States of America during and shortly after the American War of Independence (American Revolutionary War). These new settlers, many of whom were first given grants of land in Eastern Guysborough County, then known as Manchester, demanded good farmland, and were given grants along both sides of the River Inhabitants. Grant, King, McCarthy, Oliver, Proctor, Redmond, Upton and Whalen, were Empire Loyalist families to be found on those grants. The descendants of these Loyalist families can still be found within the

communities of Evanston, Grantville, Hureauville, and Whiteside.

Acadian Return

Shortly before and after the arrival of the Loyalists, some of the Acadian families had made their way back to a part of the River Inhabitant Valley, where they established small farms and did some fishing in the river. Hureauville, named after one of the families that resettled there, is the community under discussion. DeCoste and Richard were the other families that resettled in that community.

Just north of them, over the hill was Grantville, a largely Protestant community of Scottish settlers, which was using a cemetery containing the remains of some of the French settlers, who had lived in that area prior to the expulsion and burning previously mentioned. Frequently, while digging graves to bury deceased Protestant persons from Cleveland or Grantville, those doing the digging would uncover the deceased’s skeleton remains with rosaries or crosses, positive evidence of the existence of the previous French settlements. Some of the descendants of the Acadians who returned to the area, plus others from Isle Madame and Louisdale married in with the English speaking residents, so that now many residents of the community area are of mixed ethnic background. As well, within the last three decades, families of Acadian descent from the Petite de Grat area, whose forefathers may well have lived in the Inhabitants River area in previous centuries, have relocated to the area.

The Scots

Along with the resettlement of the Acadians and the grants to Loyalists, came the settlement of some Scots families like Ferguson, MacDonald, Malcolm, some of whom left Scotland because they were pushed out by greedy Lairds, who wanted their holdings for the raising of sheep -- a shameful time in the history of Scotland, known as the clearings. Descendants of these Scot settlers can still be found in the communities along the Inhabitants River, in Kempt Road, and in Walkerville and Whiteside, which are along the shore of Inhabitants Basin.

The Irish

In addition to the groups of settlers mentioned, came the Irish at the very beginning of the 1800’s. These were the refugees from the Wexford Uprising (rebellion) of 1798 who, in hiding from the British authorities, settled well back in the woods bordering on the Inhabitants Basin, until it was safe to move nearer the shore of the Basin. These refugees, most of whom settled in Rocky Bay, Richmond County, and the Margarees in Inverness County, had reason to be fearful under the Penal Laws.

Not only were their lives to be extinguished as traitors for daring to fight against the British crown, if they were unfortunate enough to be discovered by the authorities, but, according to British Penal Laws, it was illegal for them to be in British North America. These refugees were represented by the families of Doyle, Cloak, Dunphy, Hayes, Lamey, Morgan, possibly Scanlan (formerly Scantling), possibly Tyrrell (formerly Farrell), Welsh and White.

Only the family names of Doyle, Hayes, Morgan, Scanlan, and White families can still be found in the Basin - River Inhabitants communities today, though the genes of the others flow in the veins of both these, as well as in the veins of the Loyalist descents, of some of the Scottish descents, and of some of Acadian descent. The Cloaks and the Welsh’s moved away from the area, with the remaining old people dying out. The Tyrrells and the Dunphys moved to the Isle Madame area during the early 1900’s.

Some of the Irish of Whiteside had a connection with President John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s mother,

Rose Kennedy. She was born of a Wexford Uprising refugee family, the Fitzgerald family, and was actually a cousin to the Basin Road, Whiteside, Doyles* and Morgan families. Both families were descendant relatives of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, one of the most important leaders of the 1798 Wexford Uprising. The Morgans and Doyles were descendants on their mother’s side, Mary Fitzgerald, while Rose was a descendent on her father’s side. It wasn’t only because he participated in the uprising, that Mary’s son, Edward John Morgan Sr., spent the remainder of his life as a refugee hiding deep in the woods of Basin Inhabitants on a hundred acres. As close relative of Lord Fitzgerald, Edward Morgan, he believed that the Amnesty of 1803 did not apply to him, and that the British would hang, draw and quarter him, if he were to be caught. Indeed, back in Ireland all the Morgans left in Limerick had been vengefully exterminated by the English forces after the put-down of the uprising. Long after the Amnesty and their father’s and grandfather’s death, his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren kept the secret. The history of Ireland has Edward John killed at the Battle of Vinegar Hill, outside Wexford Town. If they ever knew, Ireland’s historians seem unaware that such a large number of 1798 Wexford Uprising refugees had escape to the new world, many with the help of the people from Scotland.

*It is through intermarriage with the Morgans that the Doyles can also claim descent from Lord Fitzgerald.

The most common Irish name, McNamara, to be found in the communities of the The Basin and River Inhabitants, is not one of the refugee families but are descendants of a David McNamara, who arrived in Guysborough County from Boston around 1784 - 1790, the same time as did the Loyalists, and married a Sarah Hall at Halifax,. McNamara settled, with the permission of the then General, on Boucher Island in the Basin Inhabitants. After two attempts, first as an Irishman and secondly, five years later, as a Scotsman, he was granted the island which was renamed McNamara Island. There the McNamara first multiplied and flourished, until the island could no longer support their numbers. Many of them then moved over to Evanston and Lower River Inhabitants, though a number of them moved to the United States, looking for employment. The notable Senator Robert McNamara, of the United States Senate, proudly claimed his ancestral roots in Lower River Inhabitants, Nova Scotia. McNamara Island no longer has full time residents.

Industries

Up until the early 1900’s, the communities around the Inhabitants River prospered. Many of the Proctors, some of the Malcolms and the Walkers owned clipper ships and sailed around the word in trade. The last two families ran very prosperous retail business and shipping businesses within their communities. All the other people of the communities worked in various venues: for ship owners or merchants, fished, farmed and lumbered for a living; or worked in the Richmond Coal Mine in Lower River Inhabitants, which operated until burnt out by a forest fire in 1936; or were involved in all of the first four industries, even supplying pit props for the mine. A coal mine by the name of Tide Water Coal Mine also operated for as short number of years on two separate occasions from 1928 in lower Whiteside, but was flooded out by underground water on each occasion.

The Morgans, Doyles and the Dunphys ran water driven saw mills and the Morgans and Doyles also jointly operated a water driven grist mill. A Rory Dunphy, before moving away, even ran a saw mill off a huge raft chained in the Inhabitants River. Forges also flourished in the area under both the Fergusons and the Morgans, and many of the men from most of the families were skilled carpenters who built not only in their communities, but also in Port Hawkesbury, Port Hastings and around Isle Madame.

Even after sailing ships were no longer considered as commercially viable, most of the people earned good livings in the industries mentioned. Only during the depression of the 1930’s did a few of the families need social assistance.

Due in part to the traditional Celtic interest in education, a trait shared with the loyalists, the average education levels within the communities were fairly high and there was a good work ethic. This was a significant factor when the big industries of pulp and paper (Stora Forst Industries), the Gulf oil refinery and heavywater were established at Point Tupper, Richmond County. There were very few men and women of the communities who did not find employment. The vast majority became employed in those industries or in the related retail industries. As a result, most of the residents have a comfortable living with a good number now retired on substantial pensions.

Community Names

The names of the various communities in the River Inhabitants and The Basin area came into being when the rural post office system was established, the one exception being Evanston.

Archie Walker of what is now known as Walkerville took a petition around his community to get that community called Walkerville as a postal address, while Cleveland had its name established by an act of the Nova Scotia Legislature at Halifax. Grantville and Hureauville were obviously named after the most prominent founding families of those communities, while the postal address of Whiteside came from both the fact that the White family populated that community with few exceptions, and the railway siding and station then maintained by the Cape Breton Railroad under the name, Whites Siding, later changed to match the postal name, Whiteside. The postal name Lower River Inhabitants has an obvious genesis, since that community is located near the mouth of the Inhabitants River.

The name of Evanston was born out of a bureaucratic blunder by some provincial civil servant in Halifax. The intended name of the place was Evans Town, a name that came into being when the Cape Breton Railroad needed a station name for what is now Evanston. The railroad company intended to honor its principal shareholder by naming what they believed would become a town, as a result of the railway business. However, a civil servant, sometimes during those early years, miscopied the name onto official documents, which enshrined the mistake for posterity. When the granddaughter of the original shareholder came to visit the community in the early 1920’s, she was disappointed to discover that the name had been changed. However, her disappointment did not inhibit her from investing huge sums of money into a water flooding coal mine known as the Tidewater Mine at the southern end of the Inhabitants Basin. So much of the coal taken from that mine had to be used to fuel the three steam engines that operated the five pumps, which were continuously working to reduce the flooding, that the mine did not operate after 1932. The Tide Water Mining Company went bankrupt and Miss Evans lost her investment.

The Railway

The railroad, frequently mentioned, was a major construction project in the late 1800’s, for it involved the construction of a huge trestle bridge over a fairly wide part of the Inhabitants River. During the construction of that bridge, a donkey engine steam engineer was drowned in the river, when his engine toppled of its tracks. Both the engine and his body were recovered many kilometers down the river, which shows the strength of that current. My late uncle, Percy James Proctor, also claimed that a Chinese immigrant worker also died during the construction and was buried in an unmarked grave beside the railway.

As a child, I often walked across the trestle bridge during times when the train was not chugging along the rail bed. Years before and after my ventures across, many other people also did. The railway rails and ties have been gone since the late 1970’s, and all that remains of the trestle are its concrete buttresses, which can be seen looming out of the water to the right of anyone crossing the Lower River Inhabitants bridge as they travel towards Port Hawkesbury on Highway 104.

Religion

The settlers of the Inhabitants were either Roman Catholics or Methodists, with a very few Anglican families. The latter eventually joined either the Methodists or the Catholics through marriage or conversion, when those religious denominations built Churches in some of the communities.

It is not known if the first French settlement along the Inhabitants River had a church, which would have been burnt by the British, but the likelihood is high, since they had a Catholic cemetery, which is now the United Church Cemetery in what is now Grantville. A grave containing the bones of a woman with the remnants of a rosary was found in the late 1800’s, while a grave was being dug to inter a deceased Protestant. If there was a church, it must have been close by. Only archeological digging may find substantiating evidence.

Those persons, who settled the area under British government, did not build central houses of worship until the mid-1800s. Worshipping was done in a selected home of one of the communities, when a priest or minister would visit from Guysborough, Isle Madame, or later Creignish. Marriages at first, except for those who traveled long distances to either L’Ardoise, Arichat, or Creignish, were common-law until such time as a visiting priest or minister arrived to bless the unions and establish legal recognition of the same. It was during the visits of the ministers or priests that baptisms were performed on the latest arrivals, or communion was the given and the sacrament of Confirmation was administered to those who were eligible for the same.

Those of Scottish, English, or Acadian descent could have built churches, if they had wished to, and had the funds or materials and/or skills to do so, but the Irish Catholics were prohibited from doing so under the British Penal Laws. These laws not only made their very presence in the area illegal, but forbid their building houses of worship. It wasn’t until the final penal law was repealed by the Nova Scotia Legislature in 1835 that those Irish could commence building. This last repeal saw the construction of the first Saint Mary’s Basilica in Halifax, but building elsewhere was at least fifteen years later. When their relatives, the Doyles and other Irish Catholics of Northeast Margaree began the construction of St. Patrick's Church in that community by building first the vestry as a place of worship, the Doyles, Morgan, MacNamaras, Whites, Scanlans of River Inhabitants Basin followed suite. Then in 1855 both communities, which were in communication with one another through exchange visits between relatives, began the building of the main body of each church. The Whiteside St. Patrick’s Church was opened officially for worship in the 1860’s, though services had to be supplied by the priests of neighboring parishes.

This was so until 1906, at which time a social disagreement between branches of a family took place in the church prior to Christmas Eve mass. The priest, who was from the neighboring community of Louisdale, walked in on the incident, which he considered a desecration of the church, causing him to proclaim that there would never be another Christmas Eve mass in the church. The following Christmas Eve saw no mass, and on February 6, 1908, in the early morning, the building was struck by lightning and burnt to the ground. Only the altar and a matching candle stanchion were saved. Both items were stored next door in the barn of Michael John White, in expectation of a new church being built.

By 1912, the residents of Whiteside had accumulated enough money to begin the construction of a second St. Patrick’s. Daniel O’Connell Doyle and his third oldest son, Edward Daniel Doyle took on the job of construction. Since the building was being done in opposition to the will of Reverend Father Angus Beaton of Port Hawkesbury, who had become pastor of the missions of Lower River Inhabitants and of Whiteside in 1910, and who had been by passed by the Whiteside men when they went directly to the bishop to get permission, the resulting building was different than the original. Father Beaton reduce the planned dimensions of the new church by one yard (0.91 m) in both length and width, and had them build the church facing River Inhabitants Basin. The first change reduced the building to a size that would exclude it ever from becoming a parish church, making it uncomfortably small for the size of the congregation, if all were in attendance. The second change resulted in a picturesque church facing a beautiful body of water and being against the background of a very high, forested hill. The building was consecrated in 1922, but regular Sunday mass was not held in it until 1936. Until that time, to meet their Sunday obligation, each resident had to walk or ride by horse and wagon, or horse and sleigh, past their own church, for a distance of nearly five miles { 8.3 km ) to be then ferried across the Inhabitants River, first by boat and later by cable ferry, and to then walk an additional three quarter mile { 1.25 km }, a total of 5.75 miles ( 9.58 km } to the St. Francis de Sales Church at Lower River Inhabitants. For those without horses, being forced to travel that distance on foot each Sunday was a heavy sacrifice.

On a sunny Sunday in the summer of 1936, Bishop Morrison of the Diocese of Antigonish was approach by a representative group of men from Whiteside: Daniel O’Connell Doyle, Michael R. Morgan, Joseph Roderick MacDonald, William Daniel. White, Michael John White, Duncan A.White, and Ambrose White. Bishop Morrison was at Port Hawkesbury to administer the sacrament of Confirmation to the eligible youth the Port Hawkesbury Parish of St. Joseph’s and the neighboring missions. On being approached by this delegation with the request to have Sunday mass regularly said at St. Patrick’s, the men often quoted the Scots bishop as saying, “What do you want to do, kill your priest?’ One of the men explained that they were not seeking to kill the pastor, Father Angus Beaton, through exhaustion, but they felt it was more than equally unfair to expect people to walk a considerable distance past their own church building to attend Sunday mass in a neighboring mission. The bishop agreed with their argument, but did not wish to place a greater load of duties upon Father Beaton. The solution was to reinstate St. Francis de sales as a parish. Father Alexander J. MacDonald, Father Beaton’s curate (assistant priest) volunteered to become pastor of the new parish. The bishop agreed, and St. Patrick’s Church finally had Sunday Mass, and continued to do so except for six months from October, 1969, to May of 1970, when there was a closing of the church through an unfortunate misunderstanding. The then bishop, Most Reverent William Power granted the reopening of the Church, and has had weekend mass with very few exceptions.

The Protestants of the area did not have to seek the permission of either a bishop or a minister to build their church, nor did they have to have fund raising. A wealthy Methodist merchant, William Malcolm of Port Malcolm agreed to meet the wishes of his fellow Protestants by paying for the building of a new Methodist Church at Port Malcolm, where his family and his prosperous store and shipping business were located. This church opened in the 1830’s and continued to serve the needs until around the late 1940’s. During that time it changed from being a Methodist Church to being a United Church, because the Methodist was one of the churches in Canada to join with the Congregationalists and some of the Presbyterian Churches to form the United Church of Canada.

The spirit of ecumenicalism was alive and strong along the river and the basin in the 1800’s. This was due in part that there were many marriages between Protestants and Catholics, and many of both faiths were related by blood.

The Roman Catholics from the communities along the eastern side of the Inhabitants River also received financial help from the Port Malcolm merchant, William Malcolm, in the construction of their church, St. Francis de Sales. Mr. Malcolm was married to a Catholic, Bridget Proctor of Lower River Inhabitants. When Joseph (Joe) Hureau of Hureauville approached Mr. Malcolm for a donation towards the construction of a Roman Catholic church, he was informed that Malcolm’s donation would be a dollar for dollar match for whatever money Joe collected from the Roman Catholics. Hureau did his part and Malcolm provided the other fifty per cent of the money.

The present St. Francis de Sales Church, which is also the original church, was built and consecrated as a parish church in 1875. This operated until 1909, having to that date as its last pastor, Reverend Father Maurice Thompkins, who was a first cousin to Reverend Father James Thompkins and to Reverend Father Moses Coady, the two leaders who found the Antigonish movement.

Father Maurice Thompkins was transferred to Guysborough around 1909, and St. Francis de Sales, along with the communities of Evanston, Walkerville and Whiteside who had lost their St. Patrick’s Church to fire in February of 1908, was made missions of St. Joseph’s at Port Hawkesbury. Reverend Father Angus Beaton became their new pastor and ruled his new charges until 1936. In that year, a delegation from Whiteside approached the bishop, after confirmation service at Port Hawkesbury, to get Sunday mass established in their new, fourteen year old St. Patrick’s Church.

The bishop decided he could only grant their wish by reestablishing St. Francis de Sales as a parish. Reverend Father Alexander (Alex) J. MacDonald was appointed as pastor, a position in which he remained until July of 1950. He was then transferred to St. Lawrence’s Parish, Mulgrave and replaced by Reverend Father Michael Stevenson, who in turn was replaced by Reverend Terrence Powers in 1954. Father Powers was replaced by Reverend Joseph Campbell Two years after his transfer from St. Francis de Sales, while working for the St. Francis Xavier Extension Department, Father Campbell left the priesthood to become a layman and a parent. Father Campbell was replaced by Reverend Father Edward Tobin, who also became an educator at the Isle Madame District High School at Arichat.

During his pastorship, Father Tobin directed the renovations of the St. Francis de Sales and the St. Patrick’s churches to bring them in line with the changes demanded under Vatican Council II. During this time, a bridge was also constructed over the Inhabitants River, making travel between Whiteside and Lower River much easier. With this change, Most Reverend William Power, Bishop of the diocese, ordered Father Tobin to see to the closing of the mission church of St. Patrick’s at Whiteside. Except for very few on the parish council, the parishioners of that mission were not consulted about the proposed change, and were astonished on a Sunday morning in October of 1969 to be told there would be no more masses at St. Patrick’s. The change split the communities of Evanston, Walkerville and Whiteside into two camps: those accepting the change and those against. The latter were greater in number, and withdrew their financial support of the St. Francis de Sales Parish. These angry parishioners attended services at Louisdale, West Bay Road or Port Hawkesbury instead.

Father Tobin, whom the bishop allowed to be the scapegoat for the schism, quit the priesthood, finished teaching the school year at IMDH, and moved to teach in Montreal, where he later was laicized and got married. A week after Father Tobin’s resignation, Reverend Father James MacIntyre was appointed pastor to St. Francis de Sales only. Father MacIntyre found his parish to have little financial support, since the majority of his parishioners had withdrawn their financial support over the church closing. However in April of 1970 a delegation of men from the St. Patrick’s faction met with the Bishop at the retreat house in Gardener Mines. At that time the bishop learned of the true feelings and ambitions of the offended people, and granted the reopening of St. Patrick’s Church under the same conditions as before. The St. Francis de Sales Parish once again became whole, with financial support being restored. However, some feelings of distrust lasted for some time on both sides of the issue, and future Parish Councils had to take care to give due attention to both churches.

Since the time of Father MacIntyre, the Parish of St. Francis de Sales has had as its pastors Reverend Father Terrence Lynch, Reverend Father Francis Delhanty, Reverend Father Robert Wicks, Reverend Father Robert MacNeil, Reverend Father Joseph MacLean, Reverend Father Paul Murphy, Reverend Father George MacInnis, Reverend Doctor Donald Campbell (fill in pastor for nine months), Reverend Father Peter MacLeod, and the present pastor, Reverend Father Allan MacPhie.

Education

When the area was first settled, there were no schools in any of the communities. Until 1880, anyone wishing to learn to read and write and to learn to do arithmetic had to learn at home, if a parent were educated enough to do so, or travel to St. Peter’s or some other larger community where a school had been established. My great-grandfather, James Robert Proctor had to stay for a couple of years with his mother’s sister, Mary Critchell Murray, in St. Peter’s so he could learn to read and write and to study arithmetic.

In 1880 a one room school was built at the most southern end of Lower River Inhabitants and two years later another such school, called the French School, was built between Grantville and Hureauville, to serve both communities. It was called the French School, because most of the students were French speaking Acadians from Hureauville, and the teachers at first were bilingual from Arichat.

By 1885 another one room school was built between Walkerville and Evanston, to serve those communities. The last private banker in Canada, Gordon Walker of the Walker Bank at Port Hawkesbury, located near the present Royal bank, received his basic education at that school. He used to pay ten cents to one of his classmates, Gregory McNamara, who helped him understand arithmetic better. A newer two room schoolhouse, the Walkerville-Evanston School, was built closer to Evanston, replacing the one room schoolhouse in 1949. Both my mother, Vida Proctor Morgan and I spent a number of years teaching at that school. The school was permanently closed in June, 1966, the second year after I left the area. The elementary students attended the old white multi-room school in Louisdale, with the junior high and high school students attending the new Isle Madame District High School at Arichat. This arrangement continued until June of 1979, after which time the primary through grade eight grades began attending the new Walter Fougere Elementary Junior High, which I, as chairperson of a building committee, was very instrumental in helping to bring into existence. This school, later the Evanston Site of the West Richmond Education Center, served grades five through eight until its closure at the end of June 2013.

Whiteside and Cleveland each got a one room school by 1890, both built from the same plan by a Joseph MacDonald, a carpenter from Antigonish Harbour, whose sisters had married in the Whiteside area; Sarah MacDonald was the first wife of E. James Doyle, and Jane was the wife of Timothy White. The Cleveland School operated until 1966, with the late Marcella MacCuish as the last teacher. The elementary and junior high students then attended the Point Tupper School with the high school grades attending Port Hawkesbury High. The Whiteside School continued until 1957 with Laura Hearn being the last teacher. The students then attended the old Louisdale white multi-room frame building previously mentioned, with high school students attending Arichat Convent School. When the Isle

-9-

Madame District High (IMDH) opened in 1966, serving grades seven through twelve, while the elementary grades attended school in Louisdale. With the opening of the Walter Fougere Elementary-Junior High in September of 1979, all the Whiteside and Evanston students in primary through grade eight transferred there. Grades nine and up were still at IMDH.

Initially the teachers of the one room schools had little more education than the students whom they taught. For example, a student might graduate from grade ten one year, and be the teacher of the same school the next year. Sometimes, young ladies from other communities would come to teach at those schools. These teachers were boarded in suitable homes within the respective community and would be paid maybe $200 a year, depending on the prosperity of the community and the collecting of taxes for that year. Sometimes they were not paid at all or pay years later, when money became available. Later the amount rose to $500, but this money could also be slow in coming. After 1947, the NSTU helped the teachers of Nova Scotia get more acceptable salaries on a more regular basis, with salaries becoming successively better on from the mid 1960’s.

A way of contributing to the support of the teacher was to have her or him change boarding houses each month, so the provision of board would be considered part of the contribution from the respective community members. My maternal grandmother, who was bilingual, with River Bourgeois French as her mother tongue, boarded the Lower River Inhabitants teachers on an annual basis. Since many of these teachers were French speaking also, my mother and her siblings learned to speak in a French environment, with French becoming their mother tongue. Their English speaking father was often away working on the railway. The youngsters learned to speak English when their father was home, so they all grew up being bilingual.

One man who taught in the one room schools of Richmond County was Mr. Scott Nelson. Mr. Nelson taught in Point Tupper, Whiteside and Louisdale in the early 1900’s. While at Louisdale, Mr. Nelson was instrumental in giving Louisdale its present name, for the former name of Barachois was a confusing postal address, with mail going astray between it and Little Barachois near Arichat. His suggestion to use the “Louis” part of the parish name as part of the new name was accepted when linked with “dale.”

At Whiteside, Mr. Nelson was a stern disciplinarian. Teaching was not an easy task with some country boys being quite mischievous. One day Mr. Nelson opened the outside door of the school, only to have a boy perched up in the porch rafters dump a galvanized bucket of ice cold spring water onto his bald head. The culprit was then sent to the woods to cut a strong switch for the beating he was to receive as retaliation for his offense. The offender had some days of discomfort when sitting down.

The arrival of lady teachers for the one room schools, not only contributed to the education of the respective community, but also eventually also to the populations of those communities. Very often the teacher was courted and became a married wife and mother within the community. For this reason some of the teachers had very short teaching careers. When I taught in Evanston in the early 1960’s, every second house had a former teacher as a mother. A very similar situation could be noted in the neighboring communities.

The heating of the one room schools consisted of a heating stove, often called a potbelly stove situated in the middle of the classroom. These stoves were fueled by either wood or coal, depending on the decision of the local school trustees. Frequently the laying of the fire and the lighting of the stove

were the duties of each teacher who might get help from the older students at times. It the school was drafty, those students farthest from the stove could be very uncomfortable, while those nearer the stove could become overheated.

In the earlier days of the one room schools, scribblers were not easily available, so students often did their writing on slate board, committing their lessons to memory. Later, the slates were replaced by a more plentiful supply of scribblers and lead pencils and fountain pens. Prior to the fountain pen, each desk had an inkwell bottle recessed into the desk surface. Into this inkwell, a straight pen with a metal nib could be dipped. Some boys, who were more interested in torturing some of the girls, also used the inkwells for braid dipping; an action not enjoyed by the victims.

Despite all the difficulties, learning did go on, as it does in classrooms of today. The numerous grades within the same room, created a family like learning environment, in which older students helped younger students, younger students .listened in on the work of the older students, readying them for the next grades, and students who didn’t understand the instructions from the teacher could turn, in many cases, to other students who might be able to better explain. Many well educated individuals came out of the one and two room schools of the communities around the Basin-River Inhabitants area. Some were doctor, ministers, priests, nuns, nurses, school principals, college professors, and even university presidents and superintendents of schools in Ontario. As noted earlier, the levels of education were sufficient to gain employment for many when manufacturing industries came to the strait area.

. There is much more information that could be explored, but this is sufficient for a brief history.

Lester Morgan

March 22, 2001

Revised: August 6, 2017